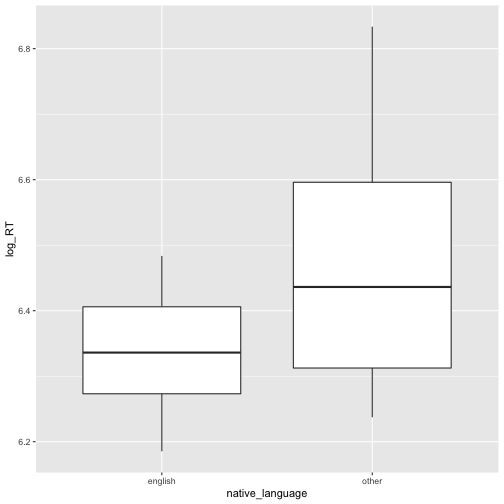

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Introduction to R ### Glenn Williams ### University of Sunderland ### 16-03-2020 (updated: 2020-03-27) --- # What is R? .pull-left[ - **Statistical programming language** used for wrangling, summarising, analysing, and graphing data. - **Free and open source**, so anyone can see how it works and add to the development of the program. - Packages and changes are vetted by reviewers, so we can be sure most things we do in R are appropriate. - Often used with **RStudio** which has some quality of life improvements. ] .pull-right[ <img src="img/R-logo.png" width="300" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /><img src="img/rstudio-logo.png" width="300" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Why Should I Care? - Veldkamp et al. (2014): 63% of articles contained at least one *p*-value that was incorrect given the reported test statistic and degrees of freedom. - In 20.5% of cases, such errors lead to **erroneous decisions** about the statistical significance of the effect. - Given that scientific claims often rely upon formal analyses, **transparency is crucial** for assessing the credibility of such claims (Klein et al., 2018). - R is rapidly developing, allowing a number of new analyses to be adopted easily. --- # How Do I Install R? ## Local Installation ## Installation and Setup - To get started, at the very least you'll have to [download R from CRAN](https://www.r-project.org/). - Choose a mirror from which to download R. Any will do. - Select the correct distribution for your operating system and then click through to **install R for the first time** for Windows, or just the most recent install version for Mac/Linux. - You'll see a new page; For Windows users, click on "Download R [version number] for Windows.". --- # What is RStudio? How Do I Install It? ## Local Installation **IDE for R**: RStudio, makes working with R and extensions to it easier. Has Git integrated for version control, and allows for easily creating and updating codebooks. - Download from the [RStudio website](https://rstudio.com/). - In the navigation panel on the website: - Select products and choose **RStudio**. - Scroll down until you see **Download RStudio Desktop**. - Click the **Download** button in the free tier and select the correct installer for your operating system. --- # Getting Started in the Cloud Alternatively, we can use [RStudio Cloud](https://rstudio.cloud) to do everything online. - Sign up for an account by clicking sign up on the [homepage](https://rstudio.cloud/). You can register easily with your Google or GitHub accounts. - This may be the easiest route, especially if your system is locked down (e.g. on University controlled computers). - This may be a little more limited than using R on your machine, but most things you need will be available. - Many guides for getting started in RStudio Cloud are available on their website. --- # RStudio Cloud This is the **workspace**, where you store your projects and access things like cheat sheets and guides on how to use R. .pull-left[ - We can start a new project by clicking the **New Project** button. - This will take a little while, but it will open up the **RStudio interface**, allowing you to perform your data tasks and analyses online. - You can rename your project once started. - We'll use this to create codebook to explain everything you need to do for this session. ] .pull-right[ <img src="img/rstudio-workspace.png" width="400" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Lesson Plan - Code along with me while I explain some basic concepts in R. - We will cover: - **Importing data**. - **Cleaning data** and performing basic data operations. - **Summarising data** with descriptive statistics and graphs. - Performing **simple linear regression** analyses. *Further explanations are available via my [R4Psych Web Book](http://glennwilliams.me/r4psych), an R course for Psychologists assuming a basic background in statistics* --- # Making a Codebook You can write scripts in R that only allow your R code and comments. However, it's often useful to have a **codebook**, which allows you to document and explain what it is you're doing. - In R, these take the form of Rmarkdown documents. - Markdown is a simple markup language that allows you to create your content and control how its displayed separately. Here's a [cheatsheet on writing in Rmarkdown](https://rstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/rmarkdown-cheatsheet.pdf). - With codebooks you can type in plain English to record your thoughts/comments, and include code chunks which, when executed, will run your R code. - It's often useful to use this notebook to explain **why you've done something** (your code should explain the how). Make your codebook by clicking **File --> New File --> R notebook**. (This will create a notebook that updates every time you save. Alternatively, html or pdf output notebooks will only update when you recompile it.) --- # Understanding the RStudio Interface <img src="img/rstudio-interface.png" width="400" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .pull-left[ <span style='color: red;'>Editor</span>: Type and edit code here. This is usually where your notebook will go. <span style='color: orange;'>Console</span>: Code is executed here. You can cycle through commands by using the up and down keys. ] .pull-right[ <span style='color: LightSkyBlue;'>Environment</span>: What variables are in your session? What are they made up of? <span style='color: blue;'>Viewer</span>: What files are in your dirctory? View any plots/help here too. (Get help by typing `?command_name` in the console) ] --- # Making a Codebook .pull-left[ - On the first creation in a project, RStudio will ask if you want to update packages, do this and you'll see a new untitled project in your **Editor window**. - Check your Files pane in the bottom right. This hasn't been saved yet. So, give the notebook a sensible title by replacing the text in `title: "R Notebook"` double quotes. - Save this with File --> Save As or Ctrl/Cmd + S. Give the file a name and save it in the base directory. ] .pull-right[ <img src="img/r-notebook-screenshot.png" width="400" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> - RStudio automatically creates an RStudio Project with your files. By default, your **working directory** is wherever your Project file is. This allows easy reading and writing of files using **relative file paths**. ] *By default, R notebooks show you how to use R code chunks and simple markdown commands.* --- # Installing and Loading Packages Many packages are available via CRAN. These make performing particular functions easier without having to write everything from scratch. Only once per project, or per machine, do you have to install a package. After this (and with every session) you need to load the packages for use. Install the packages with: ```r install.packages("tidyverse") install.packages("here") ``` Then load it with: ```r library("tidyverse") ``` It's usually a good idea to include the libraries in a code chunk at the start of your document. Do this now by making a code chunk using **Insert --> R** and typing your library functions here. If not already installed, RStudio will ask you if you want to install them. --- # Reading Data into R The `tidyverse` package makes working with your data (including reading, writing, cleaning, merging, and plotting) easier in R. `here` also makes using relative file paths easy across different operating systems. 1. First, you need to download some data. Get this from [the link for this course content on GitHub](https://github.com/gpwilliams/ioc_intro-to-r-stats). 2. Click clone or download, and download Zip. Then unzip the files and access the data via the subfolder intro-to-r/data. 3. There's one data file in here: **lexdec_raw.csv**. This looks at a lexical decision task (is the word on your screen a real word). We have some **variables** recorded such as the native language of the speaker, what the word was, and how **frequent** this word is. --- # Reading Data into R .pull-left[ - Now you have the data downloaded, you need to **upload it to RStudio**. Do so by going to Files, Upload, and then select the data file from wherever it is on your computer. Click OK. ] .pull-right[ <img src="img/rstudio-upload.png" width="200" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] - Once in your file pool, you can work with the data. But first, we must assign this to a variable. Do so by setting up another code chunk where you assign your data to a varaible by reading in the .csv file: ```r lexdec_data <- read_csv("lexdec_raw.csv") ``` - This code uses `read_csv()` to read the data. - We set the file path to grab the data by using the `here` function from the `here` package and setting the **full file name including the subfolder** in which it is located. - Finally, we assign this to a variable using the assignment operator `<-`. --- # Basic Functions in R - We've already seen how to **assign** things to variables. Once assigned to a variable, we can perform operations on our data. - **Variables** can be anything: numbers, strings (text), lists, matrices, or even data frames. - **Data frames** are very useful in R: These are **tables that can contain vectors**. The data frame can be made up of separate data types (e.g. strings or numbers), but you can't mix data types within columns without **type coercion**. - We can perform logical operations on our data as in most languages: e.g. `x < y`, `x == y`, `x != y`. - We can perform basic mathematical operations: e.g. `x + y`, `x/y`, `x*y`. - Nicely, R has some default packages for more advanced operations: e.g. `mean(x)`, `sd(x)`, `length(x)`. *More details are available at the [R4Psych page](https://glennwilliams.me/r4psych/introduction.html).* --- # Data Frames and Tibbles By default, the tidyverse functions (e.g. `read_csv`) assign your data to a variable as a tibble if read in as a table of data. - This package makes best guesses as to the data types in your .csv. - Take a look at what the data looks like in R. Add a chunk with the variable name: ```r glimpse(lexdec_data) ``` ``` ## Observations: 1,952 ## Variables: 9 ## $ subject <chr> "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1", "A1",… ## $ trial <dbl> 23, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 38, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 4… ## $ native_language <chr> "English", "English", "English", "English", "English"… ## $ word <chr> "owl", "mole", "cherry", "pear", "dog", "blackberry",… ## $ class <chr> "animal", "animal", "plant", "plant", "animal", "plan… ## $ frequency <dbl> 4.859812, 4.605170, 4.997212, 4.727388, 7.667626, 4.0… ## $ length <dbl> 3, 4, 6, 4, 3, 10, 10, 8, 6, 6, 5, 8, 9, 5, 3, 4, 8, … ## $ correct <chr> "correct", "correct", "correct", "correct", "correct"… ## $ RT <dbl> 566.9998, 548.9998, 572.0000, 486.0002, 414.0000, 483… ``` --- # Data Frames and Tibbles - We've now that we have 9 variables, with 1952 observations. We can also see the data types for these variables here. - How can we work with our data? We can extract individual columns using dollar notation. Let's see what the mean score is for RT (reaction time): ```r mean(lexdec_data$RT, na.rm = TRUE) ``` ``` ## [1] 605.762 ``` *note, we added the additional argument na.rm = TRUE to remove NAs prior to calculating the mean, otherwise this would return NA.* This is actually quite a messy data set, allowing us to see how certain functions help with real-life data in R. --- # Making Graphs in R .pull-left[ - The tidyverse has a package called ggplot2 within it used for making plots. - We build them up by **layers**. What’s the data, and how should we present it? - We always need to tell ggplot the **data source** and where to **map the variables** (e.g. on x/y axis). - We use **geometric objects (geoms)** for making them. - Let's make a box plot to explore our data. Add another code chunk: ] .pull-right[ ```r ggplot( data = lexdec_data, mapping = aes( x = native_language, y = RT ) ) + geom_boxplot() ``` ``` ## Warning: Removed 53 rows containing non-finite values (stat_boxplot). ``` <img src="intro-to-r_files/figure-html/simple-boxplot-1.png" width="60%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Cleaning Data Oh no, **we got a warning from the output**! Also, those categories have been **coded terribly**. Let's make the names more consistent. To do this, we'll use the `dplyr` package from the `tidyverse` family of functions. ```r lexdec_data <- lexdec_data %>% mutate(native_language = tolower(native_language)) ``` - There's a lot to unpack here. First, we take our data and **pipe** it into another function, `mutate()`. This allows us to change a data frame. To change our names, we set it to itself, just with all names in lower case by using the `tolower()` function. - We then assign our data back to itself. Let's check out how many names we have now: ```r unique(lexdec_data$native_language) ``` ``` ## [1] "english" "other" NA ``` --- # Making Plots in R .pull-left[ Maybe remove all reaction times with NAs, and maybe just keep the two languages we care about: ```r lexdec_data <- lexdec_data %>% filter( !is.na(RT), native_language %in% c("english", "other") ) ``` Let's check our data again. Add a new code chunk: ```r ggplot( data = lexdec_data, mapping = aes( x = native_language, y = RT)) + geom_boxplot() ``` ] .pull-right[ <img src="intro-to-r_files/figure-html/updated-boxplot-plot-1.png" width="100%" /> Better! But, the boxplot shows **many RTs are outliers**. Why? This is because we're **plotting all of the raw data**, and trials can vary a lot by subject. ] --- # Making Averages by Subject We'd like to fit a linear model to our data, but one of the assumptions is that **observations are independent of one-another**. This is not the case here, where we have several observations per participant. What do we do? We can make by-participant averages by **grouping our data** by subject and native language, and making a **summary by each group** for the mean, *SD*, and number of observations: .pull-left[ ```r lexdec_subj <- lexdec_data %>% group_by( subject, native_language ) %>% summarise( RT = mean(RT) ) ``` Let's inspect this now (gettng the first 4 rows, and all columns with square brackets): ] .pull-right[ ```r lexdec_subj[1:4, ] ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 4 x 3 ## # Groups: subject [4] ## subject native_language RT ## <chr> <chr> <dbl> ## 1 22 other 511. ## 2 24 english 530. ## 3 27 english 652. ## 4 A1 english 549. ``` ] --- # Creating Variables .pull-left[ Let's inspect our reaction times. Are they normally distributed? ```r ggplot( data = lexdec_subj, mapping = aes(x = RT) ) + geom_density() ``` <img src="intro-to-r_files/figure-html/check-dist-1.png" width="75%" /> *Oh no, that' really skewed (like most reaction times...)* ] .pull-right[ `mutate()` doesn't just change things; it can create new variables too. Let's log transform the reaction times: ```r lexdec_subj <- lexdec_data %>% group_by(subject, native_language) %>% summarise( RT = mean(RT), log_RT = log(RT) ) ``` Check our our data now: ```r lexdec_subj[1:2, 2:4] ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 3 ## native_language RT log_RT ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 other 511. 6.24 ## 2 english 530. 6.27 ``` ] --- # Our Final Plot .pull-left[ ```r logRT_boxplot <- ggplot( data = lexdec_subj, mapping = aes( x = native_language, y = log_RT)) + geom_boxplot() ``` What's it look like? Much better! But the proof will be what the residuals look like... We can then save this plot using the `ggsave` function: ```r ggsave( "logRT_boxplot.png", logRT_boxplot ) ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r logRT_boxplot ``` <!-- --> ] --- # Summarising Data in Tables Here, as before, we'll **group our data** by native language, then we make a **summary by each group** for the mean, *SD*, and number of observations: ```r lexdec_summary <- lexdec_subj %>% group_by(native_language) %>% summarise( mean_logRT = mean(log_RT), sd_logRT = sd(log_RT), n = length(unique(subject)) ) ``` Inspect the data: ```r lexdec_summary ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 4 ## native_language mean_logRT sd_logRT n ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int> ## 1 english 6.35 0.101 13 ## 2 other 6.47 0.189 10 ``` --- # Fit a Model Now we have our descriptive statistics and our plot of the data, let's fit a **linear regression to our log reaction times, split by native language**. First, we need to set native language to a **factor**. This allows us to use R's contrast coding. Let's do this then inspect the contrasts: ```r lexdec_subj$native_language <- as.factor( lexdec_subj$native_language ) contrasts(lexdec_subj$native_language) ``` ``` ## other ## english 0 ## other 1 ``` Remember, if we want to fit a linear regression with `native_language` as our variable, the **intercept** will be native_language where the value (contrast) is 0. The **slope** then represents a 1 unit change in this. *Right now, our intercept will be the mean log RT for English, and the slope will be the difference between English and Other*. --- # Fit a Model Let's use **deviation coding** to make the **intercept the grand mean** and the **slope the difference between conditions**. This is useful to know and necessary when adding multiple factors to our model. ```r contrasts(lexdec_subj$native_language) <- c(-.5, .5) ``` ```r contrasts(lexdec_subj$native_language) ``` ``` ## [,1] ## english -0.5 ## other 0.5 ``` Nice! --- # Fit a Model R uses a formula interface for defining linear models. The below formula: `log_RT ~ 1 + native_language` Says log reaction time is a product of an interept (1) and a slope for native language (i.e. the grand mean and your native language determines your reaction time score). ```r lexdec_mod <- lm(log_RT ~ 1 + native_language, data = lexdec_subj) ``` What are the coefficients of the model? ```r lexdec_mod ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = log_RT ~ 1 + native_language, data = lexdec_subj) ## ## Coefficients: ## (Intercept) native_language1 ## 6.4095 0.1218 ``` --- # Inspect the Model To see the model output, including parameter estimates and test statistics, we use the `summary()` function: ```r summary(lexdec_mod) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = log_RT ~ 1 + native_language, data = lexdec_subj) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -0.23308 -0.08109 -0.01732 0.12077 0.36311 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 6.40951 0.03054 209.848 <2e-16 *** ## native_language1 0.12181 0.06109 1.994 0.0593 . ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.1452 on 21 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.1592, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1192 ## F-statistic: 3.976 on 1 and 21 DF, p-value: 0.05929 ``` --- # Interpret the Model - The model output states that the grand mean is around 6.41 on the log scale, and the difference between conditions is around 0.122 on the log scale. - Only the intercept is **significantly different from zero**. - This means that we we **cannot reject the null hypothesis** that speakers don't differ in terms of their lexical decision times by native language. - Thus, although there is a numerical difference in scores, this is **not sufficiently suprising compared to zero** for us to say this difference will be present in the population. - Can we confirm where these values come from? --- # Interpreting Model Estimates ```r lexdec_summary ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 4 ## native_language mean_logRT sd_logRT n ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int> ## 1 english 6.35 0.101 13 ## 2 other 6.47 0.189 10 ``` What's the difference in scores? Does it match our model output of around 0.122? ```r lexdec_summary[2, 2] - lexdec_summary[1, 2] ``` ``` ## mean_logRT ## 1 0.1218099 ``` --- # Saving our Output We already saved our final plot. But how do we save our model output and descriptive statistics? For the descriptive statistics, we just use `write_csv()`. ```r write_csv(lexdec_summary, "lexdec_summary.csv") ``` However, for the model output, we need to get this in a tabular format first. One useful package for converting statistical output to a table is the `broom` package; install and load it (probably best at the start of your notebook). ```r install.packages("broom") library(broom) ``` --- # Saving Model Output Let's see how `broom` works, using the `tidy` function (I'll round these values, too): ```r lexdec_mod %>% tidy() %>% mutate_if(is.numeric, round, 3) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 6.41 0.031 210. 0 ## 2 native_language1 0.122 0.061 1.99 0.059 ``` *p-values are often reported as 0 when rounded from very small numbers, but can never be exactly 1 or 0 as they represent probabilities from which we can't ever be certain about their true value; thus report p = 0 as p < .001.* Save our tidied output with: ```r write_csv(tidy(lexdec_mod), "lexdec_mod.csv") ``` --- # Accessing our Research Products - You should now have a list of files in your **file pool**, including your raw (input) data, your descriptive statistics, plot, and model. - You can export these by going to your **File pane**, clicking on a file, clicking **More** --> **Export...** and then choosing a name for your file. You can then download this to your computer. <img src="img/rstudio-export.png" width="300" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> You may want to download all these separate files (e.g. for use in another document), or to download your HTML/PDF output for your codebook for sharing with others. --- # Final Remarks - This was a really **quick crash course in R**, so not all concepts could be explored fully. However, I hope this was a nice introduction to just how much you can do, and quickly, with R. - Using **R notebooks** like this allows you to document everything you've done, so you (and others) can confirm the accuracy of your work. - We've seen how to filter and clean our data, how to make summaries of our data, and how to plot and model our data. - The R syntax can be difficult to learn, but with the `tidyverse`, we can make use of a number of plain English verbs for working with data. - To learn more, I suggest you check out a number of useful, free resources such as [r for data science](https://r4ds.had.co.nz/) and [r4psych](https://glennwilliams.me/r4psych/) (which adapts r4ds from a psychologist's perspective). --- # Bonus Slide: Checking Model Fit Were we right to fit a model on log transformed reaction times? What do our residuals look like? .pull-left[ - These seem fine, but there may be an outlier in our data (at the top right) indicating our 19th participant is quite different from the rest. - Here, we might be justified in checking individual responses from this participant. If we're really concerned and don't want to filter people out, we may alternatively use a **non-parametric test** (e.g. on ranked observations). ] .pull-right[ ```r plot(lexdec_mod, which = 2) ``` <img src="intro-to-r_files/figure-html/check-resid-1.png" width="75%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ]